1,000 Foot Overview:

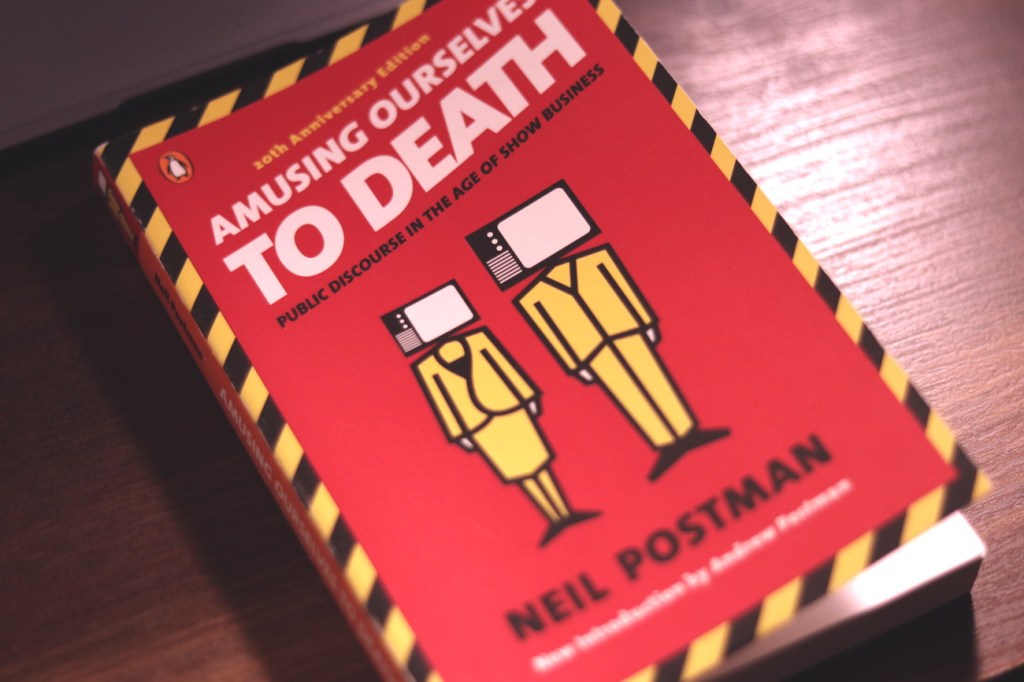

In this 1985 work, Neil Postman makes the case that TV is altering the form and content of American discourse and culture for the worse.

The Medium Is the Message

According to widely accepted wisdom, no technological development or tool is good or bad in itself. Rather, any technology can be used for good or bad. Marshall McLuhan’s famous phrase “The medium is the message” was meant to reveal the naivety of this idea. The truth is that technology is never neutral. All forms of media have biases, and these biases encourage different kinds of content, thinking, and ultimately, culture. Postman argues that for the two hundred years prior to TV becoming America’s primary mode of communication, there was an Age of Typography in which the printed word held a monopoly on discourse in America. Printed text had certain biases and encouraged certain kinds of thought, which produced a culture with certain characteristics:

- required the ability to think conceptually, sequentially, and deductively

- emphasized reason and order

- discouraged contradiction

- encouraged objectivity and detachment

- favored toleration for delayed response

However, television has very different biases from the written word, and its widespread adoption as the primary means of communication in the United States is leading to a very different kind of culture. Now Americans have entered a new age: the Age of Show Business.

The Age of Show Business

Many people have attempted to speak about the influences of television on culture, but they have not gone far enough in their efforts. In order to truly grasp the influence of television, it has to be understood as an epistemology.

Epistemology–a theory of knowledge or ways of knowing

TV has led to a world of decontextualized knowledge that has little real value to people. During the Age of Typography, knowledge was directly related to the contexts of people’s lives. All of this changed with the invention of the telegraph and photograph, which created the possibility for rapid transmission of information from across the country. This change has now reached its peak in TV, where people are bombarded by information from every corner of the country and the world, but all of it has been removed from its context, reducing it to trivia. Now, new contexts have to be invented (such as games) to give a use to this otherwise useless knowledge.

The second impact of television is that it encourages the viewer to believe that all things are to be evaluated according to their entertainment value. TV does little harm when it contents itself to show junk. The problem appears when TV tries to present itself as a medium for serious discussion of serious topics. But because it is a medium fundamentally suited for dynamic imagery and sound, TV programming is naturally designed to play to these strengths. Exposition, sophistication, and propositional content are all discouraged by the medium. No matter what content a TV program attempts to provide to the viewer, it will have to be made entertaining.

Not all things are entertaining, nor should they be, but this is what TV requires of them. As a consequence, since television has become our primary mode of discourse, it has programmed people to believe that all things that appear to them on TV should be entertaining. This has produced an general degradation of discourse and negatively impacted many different fields from politics to education to religion.

What Can be Done?

Postman insists that it is very unlikely that the TV genie can ever be put back in the bottle. Americans are not going to give up television now that it has become their way of life. However, by educating the public about television, the way in which it alters perception and culture and the ways in which it is totally inadequate for certain subjects, there is hope that the damage that it has done can be repaired. As he sees it, this task can only be accomplished by the schools.

Ch. 1: The Medium Is the Metaphor

At different times in history, different cities have embodied the spirit of America. Boston, New York, and Chicago have all, at different times, represented the ideals of the moment. In 1985, Las Vegas should be considered the representative city of an American culture that is devoted to entertainment and reduces all discourse to its power to amuse.

In various ways, American culture is dominated by superficial standards of attractiveness over substance. Looking good on camera is the key to success for news presenters and presidents alike. Whether they are journalists or theologians, America favors those with the power to entertain.

There have been many explanations of this “descent into vast triviality,” but the purpose of this book is to suggest that it can be explained (in large part) by the effect that our methods of communication have on what ideas can be easily expressed and, therefore, what ideas will become culturally significant.

You couldn’t, for example, express a philosophical argument using Native American smoke-signals, for obvious reasons. But, for less obvious reasons, it is also impossible to do political philosophy on television because television is a medium that prioritizes visual images over words.

The concept of the “news of the day” could never have existed without the medium of the telegraph. It was only through the development of this extremely (for its time) rapid form of communication, that it was possible for people to attend to events happening on that day in other parts of the country. Without the medium, the form could not exist.

Many people believe that all mediums of communication are neutral. They don’t contain their own content. However, Marshal McLuhan’s famous phrase “The medium is the message” expresses the opposite idea. Different technological advancements and different forms of media affect what kind of content can be expressed through them because they affect the orientation of our thoughts and how we express them, and this, in turn, affects culture. They can also include their own content by altering how we perceive the world.

Metaphors

People have always understood the world through metaphors. Is the mind a blank slate to be filled or a garden to be tended? Is life a line into the future or a circle reflected by the cycles of nature?

The invention of the mechanical clock forever changed the way that humans understood and experienced the passage of time by providing a system of independent, measurable units of time: seconds, minutes, hours. This way of thinking was extremely significant to the cultural changes caused by the Industrial Revolution.

The invention of eye-glasses suggested that humans did not have to be satisfied with what nature had given them or with the degradation of old age. It provided a new metaphor for humanity to understand itself. People came to think of themselves as malleable and improvable through the use of technology. This concept may itself have led to the gene-splitting research of the 20th century.

The purpose of this book is specifically to examine the way in which the medium of television has altered the content of American discourse. As America moves past the Age of Print into the Age of Television, it is important to look at the special advantages that the medium of print provided and how those advantages have been lost or altered by the visual medium of TV.

“Our media are our metaphors. Our metaphors create the content of our culture.”

Ch. 2: Media as Epistemology

This is not just an elitist complaint about “junk” television. The best thing about TV is its junk. The real problem is when TV presents itself as the carrier for important conversations. Previous critics have not taken TV seriously enough. A serious discussion of TV must look at it as an epistemology, and this is what previous critics have not done.

Epistemology–the study or a theory of the nature and grounds of knowledge especially with reference to its limits and validity (Merriam Webster)

Speech, like print or TV, is a medium for communication. Cultures past in present which communicated primarily through oral speech considered the quality of a person’s speech to be an indicator of their ability to express truth. When Socrates was defending himself in his trial, he began by apologizing for the fact that he did not have a prepared speech, and that he will stumble in making his case. He asked that this not be held against him and promised to represent the truth despite not having a strong rhetorical style.

To modern audiences, this seems extremely reasonable because we are accustomed to thinking that rhetorical style is mostly ornamental and that truth is truth regardless of whether it is expressed with style. However, in a primarily oral culture, this is not the case. There is a good chance that many of the jurors that condemned Socrates did so because they believed that a poor rhetorical style indicated a lack of truth.

Today, the written word is usually thought to be a more serious carrier of truth. The spoken word is more casual and should not be held to the same degree of scrutiny. Furthermore, there is an epistemological prejudice in favor of what can be quantified. Information expressed through mathematics is often presumed to provide a higher quality of information that which is not.

How Media Affects Perceptions of Intelligence

Different modes of communication require different things and labels different abilities as “intelligence.” In an oral culture, intelligence is associated with the ability to remember many different stories, parables, and aphorisms because those are the truth contents of that culture. In a reading culture, memory is charming but mostly irrelevant and not considered a sign of high intelligence.

Instead, perceptions of intelligence in a reading culture are determined based on the abilities that effective reading requires:

- control of the body and mind to sit still and concentrate on the text

- the ability to hold the line of an argument in one’s mind until its conclusion

- an understanding of and ability to navigate abstract concepts

Three Clarifying Points

- This book does not argue that media causes changes in the structures of people’s minds or their cognitive capacities. This may be true, but it is unnecessary to the argument of this book, which is concerned with the structure of discourse, not the minds of individuals.

Related Reading: Though Postman does not tackle this subject, it has been covered recently in the 2011 book The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains by Nicholas G. Carr. From reduced attention spans to lower retention to an overall reduction in our capacity for deep thinking, Carr makes the case that the internet has had a radical effect on cognitive abilities.

- The epistemological change described does not (and may never) apply to everyone and everything. TV does not have to erase all other forms of media in order to have the profound effect described. It simply needs to reach a certain “critical mass” of importance or popularity within a cultural environment.

- This is not a “total assault” on TV, which like print has produced benefits along with disadvantages. TV’s value as a source of comfort for the elderly and infirm, a tool for using emotion to sway public opinion, and a theater for the public is duly noted. This books merely argues that, on balance, the overall impact of TV on American culture and discourse has been negative.

Ch. 3: Typographic America

It is hard to overstate the extent to which Colonial America valued the written word. In the 17th century, literacy rates among men in England did not exceed 40%, while an estimated 89–95% of American men and as much as 62% of American women were literate. Some of this incredibly high literacy rate was due to religious influences. The Calvinist Puritans that comprised the first American settlers placed enormous importance on education and the study of the Bible for self-improvement and resisting the snares of the devil.

Important: During much of this period, the written word enjoyed a complete media monopoly over the population. Radio and even photography were yet to be invented.

Just as interesting, this culture of literacy was essentially classless. Reading was not considered an elitist activity and both laborers and aristocrats read widely. The popularity of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense gives some sense of how pervasive this culture of literacy was. To reach the same level of popularity achieved by Paine, a book in 1985 America would have to sell 24 million copies. In fact, the only media event that could (at the time of writing) compare in terms of collective attention would be the Super Bowl.

Newspapers and pamphlets (another important part of Americans’ reading diet) grew rapidly in popularity and circulation. Between the years of 1730 and 1800, the number of regularly published newspapers in the colonies grew from seven to 180. Novels were so popular that when Charles Dickens visited America in 1842, he received the kind of reception that is today associated with superstars.

European visitors to America were impressed by this highly literate culture–in particular its lack of class distinctions–and by the way it affected American discourse. Alexis de Tocqueville commented in amusement that “An American cannot converse, but he can discuss, and his talk falls into a dissertation.” Even their habits of speech followed the structure of the printed word. But the influence of the written word didn’t just affect the form of American discourse; it also affected its content.

Ch. 4: The Typographic Mind

The debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglass were the stuff of legend. One of their lengthier debates lasted for a combined seven hours–not including an intermission for the crowd to have dinner. The fact that audiences were able and willing to listen to such a thing indicates something about the type of culture which dominated America at this time.

During this period, attitudes towards reading were universally favorable. Having little leisure time, colonial Americans did little casual reading. Instead, what reading they did was serious, intended to educate and inform them on important matters. Reading was imbued with a sense of sacredness. Because of print’s monopoly over media, it was also the only means of following or participating in the public discourse. This participation was thought to be the duty of all citizens, and the Founding Fathers clearly believed in its necessity. Voting restrictions against those who owned no property were often overlooked; restrictions on those who could not read were not.

Typographic Communication

Postman refers to this two-hundred-year period as the Age of Exposition. Exposition is a mode of thought, learning, and expression, and typography has the strongest possible bias in favor of exposition:

- requires the ability to think conceptually, sequentially, and deductively

- emphasis on reason and order

- despises contradiction

- encourages objectivity and detachment

- favors toleration for delayed response

Typographic communication has certain characteristics. The most obvious and also most important of these characteristics is that it has content, some idea which is being put forth by the author and demands a response from the reader. The written word requires readers to be able to follow the line of an argument for long periods of time. This encourages analytic thought as each part of an argument can be separated and scrutinized. More than other forms of media, it addressed itself to the rationality of the reader.

Note: The influence of expository thought could even be seen in the newspaper advertisements of the time: full paragraphs which attempted to persuade readers by rational argumentation. Contrast this with the terse, visually-dominated ads of today which focus on emotional/psychological manipulation.

But this Age of Exposition which was enabled by the dominance of typography would eventually be replaced by the Age of Show Business.

Ch. 5: The Peek-A-Boo World

Two technological developments laid the foundation for the Age of Show Business: the telegraph and the photograph. The first separated communication from transportation. Previously, information could only travel as fast a person could carry it, but this was forever changed by electricity. Now, information could move at incredible speeds. This new possibility enabled the rise of the “news of the day”–information gathered from all across the country–and a class of newspapers devoted to spreading it to the public.

In this environment, information was characterized by three characteristics:

- Irrelevance – most of the information people encountered had no relationship to their real contexts and served no obvious function for them.

How often does the morning news provide you with information that causes you to change your plans for the day or helps you solve some problem you are working on? - Impotence – people are inundated with information about subjects over which they are entirely powerless.

What do you intend to do about inflation or the latest international conflict? - Incoherence – where typographic knowing always involved embedding facts within a larger understanding, the “news of the day” world of disconnected and fragmentary facts required no unifying perspective to make these facts meaningful.

This change in media created a change in epistemology and how people related to the information that they received. Information became a commodity of novelty and curiosity, which required the invention of new contexts in which it could be put to use: crossword puzzles and games like Trivial Pursuit and Jeopardy.

The Age of Exposition might have withstood this attack, but the telegraph and the type of epistemology that it created was aided by a second major event: the invention of photography. Photography created the illusion of context by supplying a sense of concrete reality to fragmentary facts which otherwise might have seemed unreal. In truth, photography removes particulars from their contexts by design (no one ever speaks of photographs being “out of context”).

Together, these technologies made possible a “peek-a-boo world” in which information and events could be presented to audiences as objects of novelty or curiosity and then be immediately forgotten because the information could not be connected to any real context of the viewer.

This peek-a-boo world, this world of useless information, was perfected by television, and television is now the center of a new American epistemology which touches every area of life. TV has become such a pivotal part of American culture that people no longer discuss TV; they discuss what is on TV. It has been so fully accepted that it is essentially invisible. Its naturalness to us is a measure of how much we have been changed by it.

Ch. 6-7: The Age of Show Business / “Now…This!”

Now that it’s been established that TV has produced a culture radically different from the culture that was produced by the printing press, what are the characteristics of that culture? What modes of thinking and kinds of conversations does it encourage?

All forms of media have a bias towards certain kinds of use. A TV may be used as a light source, or it may be used to display the printed word on the screen, but the bias of TV is to be used in exactly the way that it is used: a source of entertainment which communicates primarily through visual images and demands little from its user.

The World as Entertainment

Part of what makes TV threatening to discourse is the fact of how widely it is used. People turn to their TVs for all things, from getting the weather report to learning about the latest baseball game to learning about policy discussions and scientific advancements. But above all, people turn to their TV to be entertained, and this is the problem.

Entertainment itself is not a bad thing; however, the problem with television is that it presents all of the world and all subjects in it as entertainment. The effect is that entertainment becomes the standard by which all things are judged.

For instance, news broadcasts may document horrible events, but the smiling anchors and their invitation to “join us again tomorrow” signals to the audience (whether they mean to or not) that all of it is unserious. All of it is merely “good television.”

TV’s inability to exceed this limitation is seen most clearly when it tries sincerely to do so. Postman uses the example of televised “discussion” which aired in 1983. The guests consisted of serious intellectual figures (Henry Kissinger, Carl Sagan, William F. Buckley, Elie Wiesel, Robert McNamara, and others) and covered important topics. It was even aired without commercial breaks.

But the limitations appeared in spite of these efforts. The host would call on each guest in order and allow them to speak for four minutes, so if one wished to respond to something that someone else had said, they would have to wait their turn. The flow of natural discussion was made impossible, and each of the speakers simply used their time to speak about their own topic of concern. A genuine discussion involves time spent thinking or struggling to articulate ideas. It involves thinking, and because thinking is not entertaining to watch, it was avoided. Rather than a discussion, what was produced was a series of monologues that reflected the fragmentary nature of the medium.

This does not mean that TV never shows people thinking, just that it is the bias of the medium to prioritize what is visually stimulating over the content of ideas. It also does not mean that television never permits the kind of long-form, nuanced presentation that is characteristic of typography, just that programs which attempt this will pay a steep price for being “bad television.” The shows that do well on television conduct themselves by the rules of show business, and eventually, show business is all that is left.

Now…This! Effects of TV on Journalism

In newscasts of the period, this phrase often served as a clumsy transition from one story to another totally unrelated story and revealed the fragmentary nature of the news, where the events are chosen for reporting based on their ability to capture the audience’s attention. This is just one of many changes that TV has had on how people receive and absorb information about the world.

The disconnected reporting itself gives the impression that no story can be very serious since it must be wiped from memory as soon as the anchor transitions to the next story. The presence of music and the calm, friendly attitudes of the anchors implicitly signal to the viewer that none of this can be terribly serious. But the audience is also a participant in this act; they would be deeply disturbed if an anchor were to express horror (even appropriate horror) at what they were reporting.

The ultimate example of the “Now…this!” mentality is the commercial. When news describing horrific events can be followed by cheery advertisements for fast-food, it cannot help but influence the viewer’s perception of the importance of events.

Additionally, the fragmentary, decontextualized nature of the news seems to have caused a reduction in people’s capacity for recognizing contradictions and understanding their importance. In a world of decontextualized fragments of information, contradiction does not matter because (in the eye of the beholder) it does not exist.

The end result of this media environment is that viewers who attempt to inform themselves by watching the news are more likely to receive disinformation in the form of innumerable disconnected facts which do not provide a coherent or contextual understanding of events, but instead provide entertaining diversions.

Ch. 8: Shuffle Off to Bethlehem

Like journalism, religion has been radically altered by television and its tendency to reduce all things to their entertainment value. TV preachers claim that it is an invaluable tool for spreading the message of Christianity, saying that the message is the same and all that has changed is the mode of delivery. But it is naive to think that a change in delivery does not affect the message. The enormous audiences TV gives them access to has blinded religious leaders to the numerous ways in which the medium mutilates the message.

Lack of Sacrality

Essential to authentic religious observances is the sacredness of the area in which it occurs. This does not require that all religious services occur within churches or synagogues. Almost any space can be made sacred if it is divested of all of its profane uses. This requires certain rituals and the observance of certain behaviors, like refraining from eating or casual conversation. This sacredness creates the sense of otherworldliness and enchantment that is the bedrock of religious experience, and it cannot be achieved over a television. People will do all the things that they normally do while watching TV, preventing any aura of spiritual transcendence.

Idolatry

Because TV removes so many vital aspects of religion, there is a greater risk that more attention and more importance will be given to the preacher than to God. This is especially true when the importance of the sermon’s entertainment value is considered. Religious programs imitate secular programming in format and production values. They also take from secular programming the objective to give the people something they want.

Triviality

TV programming aims to give people what they want, and religious programming on television is no different. As the executive director of the National Religious Broadcasters Association stated, “You can get your share of the audience only by offering people something they want.” But religion has never been about giving people what they want. Instead, it has always attempted to give people what they need. This difference is critical.

Christianity is a serious religion, but its modification to the rules and values of television has turned it into a different, trivial religion.

Ch. 9: Reach Out and Elect Someone

TV has, unsurprisingly, affected politics as well. Certain things can be presented on TV with little risk of distorting the facts of the matter. For instance, it is very unlikely that an audience can be convinced that the footballer who misses a goal has helped his team by missing it. In sports, the rules are too well known, the standards are too clear, and the outcomes are too obvious for ambiguity. However, politics is not so transparent. Its complexity makes it far easier for TV to degrade. If politics is now a business like show business, then having virtue is far less important than appearing to be virtuous. The most fitting metaphor for political discourse is now the television commercial.

Commercials in Politics

Prior to the dominance of TV, advertisements were frequently lengthy (by the standards of the average commercial) propositional statements of a product’s features and benefits intended to convince a rational consumer of its worth. Capitalism itself takes for granted the rationality of consumers, so it is hard to overstate the threat that commercials pose to the theory of capitalism.

Commercials don’t address the viewer through propositional statements of value, but through images and appearances. They target the emotions of the viewer, not his reason. They highlight the ways in which he may feel inadequate or unfulfilled, and subtly (without any use of direct proposition) persuade the viewer that their product will address these deep needs–which of course, they will not. In this way, commercials are like instant therapy, whose effects are only slightly more lasting than the commercials themselves.

To demonstrate the efficacy of commercials for politicians, Postman uses the example of the Senate race between Jacob Javits and Ramsey Clark. Clark addressed the public with a series of published papers outlining his positions and policy ideas on a host of subjects. They were detailed, well-informed, and filled with relevant facts and coherent arguments. Javits did not publish anything like this for his campaign. Instead, he relied on short TV commercials which did next to nothing to inform the public about his policy prescriptions, but did a lot to give him the appearance of virtue and experience. Javits won in a historic landslide.

Additionally, TV has allowed politicians to fold themselves into the world of entertainment, making appearances on various programs and venues. This confuses the subject even further by making politics a game of personalities rather than issues and policies.

Political commercials attempt to latch onto the areas of the viewers’ greatest discontent, allowing them to project their anxieties and the hopes for the relief of those anxieties onto the politician. Politics is always about leveraging one’s interests, but TV has made many of these “interests” are symbolic and psychological.

Ignoring History

Political understanding must necessarily include historical understanding, but in the Age of Entertainment, this is sorely lacking. Part of this is due to the fact that Americans are bombarded by floods of information about the current moment, but because this information does not fit into any greater narrative or context, it is quickly forgotten. But this is not the whole cause.

If people have begun to lose their interest in historical knowledge it is because it has come to seem irrelevant to them. The reason for this is simple. In the imagistic, present-centered world of TV commercials, there is no history, no past worth speaking of.

Orwell had envisioned a dystopian future in which totalitarian governments would be able to alter history and erase the past from memory. But it seems that Aldous Huxley’s vision was accurate. There is no need to erase the historical record. One can simply provide the public with so many distractions and amusements that they do not care to look.

The use of entertainment to pacify the masses is a well-known tool for tyrants. TV has perfected this tool.

Ch. 10: Teaching as an Amusing Activity

When the classic children’s education show Sesame Street first appeared, it was immediately clear that it would be successful. Not only was it entertaining to children, but it appealed to parents and educators who wished to believe that such programing could teach children how to read and get them to enjoy school. In retrospect, it is clear that programs like Sesame Street did more to undermine traditional schooling by convincing students that they should only enjoy school when school looked like Sesame Street.

Some may claim that TV can have its value as a learning tool because it teaches children the alphabet or how to count, but the specific subject matter is less important than what it teaches them about learning in general and how learning happens.

Television does not just teach children the specific content that it explicitly tries to teach; it teaches them how to be good TV-watchers. TV programs, in turn, do not aim, first and foremost, to help their viewers grow; they seek to entertain. The three commandments of TV are as follows:

- Thou shalt have no prerequisites–TV shows are able to be enjoyed by anyone at any time. There is no requirement that they come to the show with any particular previous education (except maybe being able to speak the language).

- Thou shalt induce no perplexity–Perplexity and sophisticated thinking is the a sure road to failure on TV. TV programs are meant to appeal to the viewer as he or she is. The goal is contentment, not growth, and so TV will not seek to mentally strain the audience.

- Thou shalt avoid exposition–Instead of exposition, TV opts to tell stories through dynamic images and music.

Education devoid of prerequisites, perplexity, and exposition is more properly called entertainment, and the most troubling effect of TV on education has been to instill the belief that education should be entertaining.

There are many good reasons to believe that education should not be entertaining. Education entails being tested and having your comprehension strained. It requires the learner to step outside of themselves and of the present moment. It requires that they be able to grow. While these things may be ultimately fulfilling, none of them are immediately entertaining.

Despite those who claim that children learn best when information is presented to them within a dramatic context (as it is in television shows), reputable studies cited by Postman show that, in fact, television does not improve learning. Those who absorb information through TV retain far less of of it when compared to those who get that information through the printed word. Furthermore, TV does not cultivate high-order thinking skills to the same degree that print does and it is not as effective at communicating sophisticated ideas.

This contradiction between the aims of TV and the aims of education reveal a deep incompatibility between the medium and what it is trying to be used to do. It would not be so bad if TV was simply not very good as a tool for education. The problem is that when education is expected to be entertaining, all educational content that is not entertaining (the majority of it) is undermined.

Ch. 11: The Huxleyan Warning

In the 19th century, two authors provided different visions of dystopian futures in which humanity has been enslaved. The first, and more famous, was George Orwell and his haunting portrait of the totalitarian state in 1984. The future that Orwell imagined was a prison in which nothing fell outside the control of the state. However, in his book, Brave New World, Aldous Huxley provided a vision of a future in which the world is not a prison but a carnival of mindless distraction and trivia.

American appears to be far closer to fulfilling the warning of Huxley than of Orwell. Everything about the American spirit has well prepared them to recognize and oppose Orwellian threats, but they appear to be totally naive to the risks of a power which seeks to degrade and impoverish them by supplying them with a world of endless distraction and entertainments such as the TV has provided.

What’s more, these changes have not come from any explicit ideological movement, which would make it far more visible. Instead, it is the unintended consequence of how a new medium has altered public discourse.

There is a long history of new technologies altering patterns of social life in far-reaching and unpredictable ways. At previous points in history, people could be forgiven for failing to understand this, but by now we ought to know better.

Suggestions for Moving Forward: A Race between Education and Disaster

In discussing possible strategies for improvement, Postman begins by explaining what won’t work. Among these false solutions is the Luddite position of trying to put TV “back in the box,” so to speak. This is naive and unrealistic. Americans, having paid for them and gotten a taste for them, are not going to simply throw their TVs out. Other similar strategies, such as communities refraining from watching TV for a month, are praiseworthy, but they fail to address the root of the problem.

As stated previously, culture isn’t threatened by TV’s junk. It is threatened when TV presents itself as a mode of discourse for serious subjects. In order to combat this, the only real answer is education. People must be made to see the ways in which television alters discourse and culture. They must be made aware of the messages that different forms of media carry. There are two possible ways in which this education might be accomplished: through television itself or through the schools.

The first suggestion is patently nonsensical. Any television program attempting to capture enough of the public’s attention would have to conform itself to the rules of show business and would end by succumbing to the very same problems that have already been discussed. The only serious option is for this education to be accomplished in the schools. It is acknowledged that this is a desperate answer, that it’s success is uncertain, but it is the only one available to us.

Leave a comment