For the past several months, James Lindsay has been on a crusade against something that he is calling the “woke right.” In general, I think that this discourse has produced way more heat than light, and to be truthful, if you follow me on Twitter, I’ve been pretty guilty of a fair amount of that heat. (To be fair to myself, when the person pushing the discourse is as obnoxious as James Lindsay has been, I think it comes with the territory.) But beyond this particular conflagration, I’ve been thinking about a growing divide in the coalition which for some time has opposed the “woke” (I’ve always hated this term) left.

On one half of this schism is what Lindsay has labeled the “woke right” and he claims that what makes them woke is that they are all using the same framework: critical theory. And the base formula that all of these movements use is that of conspiracy: there is some group in power that is pulling strings and preventing people from seeing the truth. Of course there’s a problem with James’s use of this idea because he himself sounds a little bit nutty and conspiratorial when he talks about all of this stuff too. In fact, what has he been doing for the last ten years but trying to expose a conspiracy within academia to enact Marxist ideas, the so-called “long march through the institutions”? Of course, when Lindsay is called out on this point, he defends himself by arguing that his conspiracy theory is accurate. Interesting how he affords himself that avenue, but I digress.

But in contrast to these “woke” views, Lindsay posits his own ideology of “American Realism.”

Whether or not he is calling himself a liberal, liberalism is clearly baked into what he wants. That would imply that his liberalism is grounded in this thing that he’s calling “American Realism”,” and that means this foundation needs to be very solid.

Is it?

To even answer the question, we need to know more about what we’re talking about. And that’s a problem because James has just made the thing up. If you were to google “American Realism” you’d find out that it was an artistic and literary movement, not a a school of philosophy. Let’s take this post by a user that James follows and frequently re-posts as a good starting place for examining this “American Realism.”

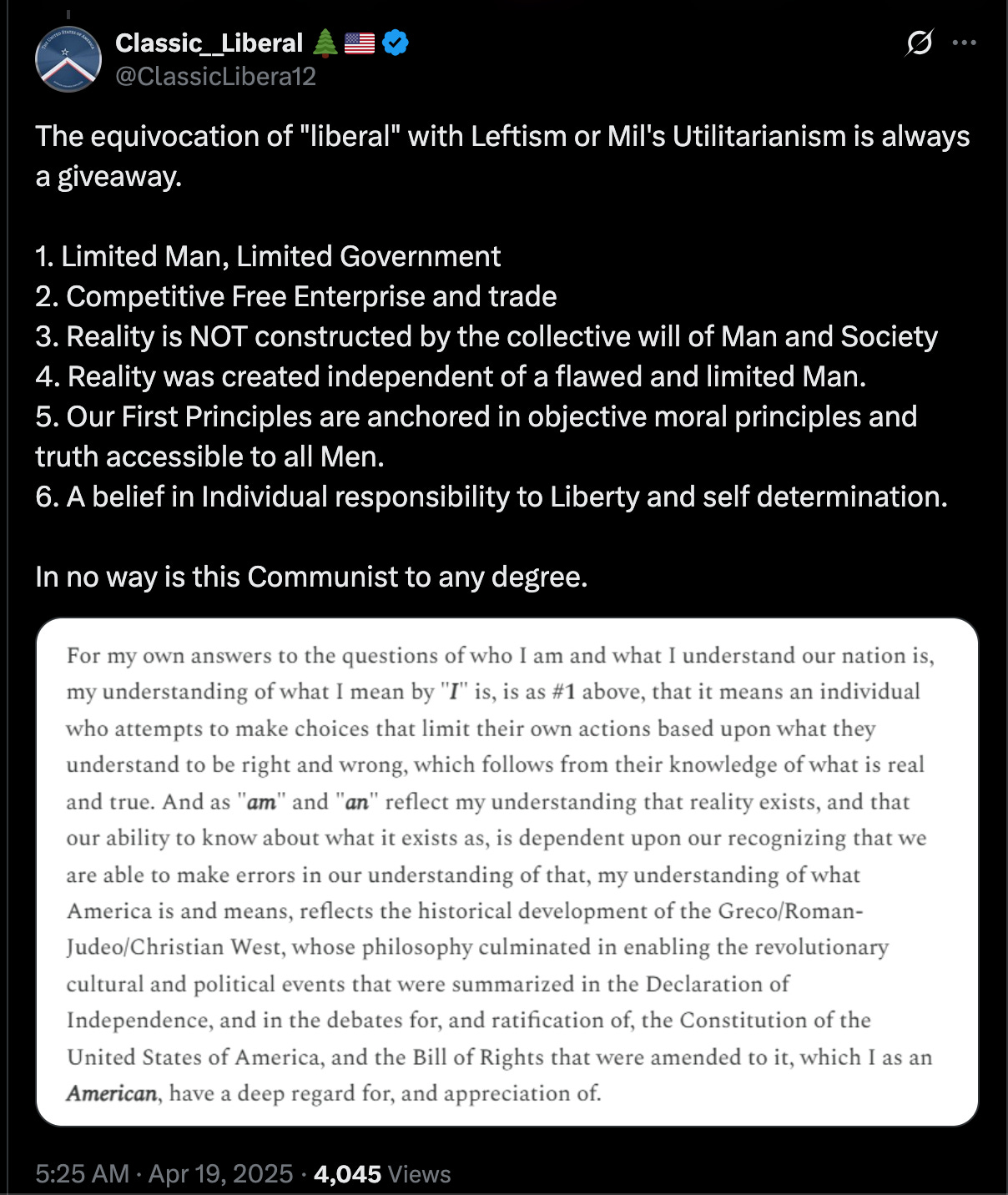

Edit: I realized that the connection between Realism and this list of items might not be immediately clear. Here’s another tweet from the same user pointing the direction. The gist: classical liberalism is built off of the back of Realism. The tweet pictured below combines the core pillars of both.

I think it’s a pretty decent expression of the major points of concern.

You can sort these points out based on which of them are related to Liberalism and which are related to Realism. Points 1,2,4, and 6 are former, and I have basically no gripe with them.

But when we look at point 3 we get problems because, while it is technically true, it is wrong in every practical sense.

Man doesn’t create reality, but it is simply a fact that our institutions create this thing called “reality” in everybody’s heads. If you were a European prior to 1500, “reality” was that the Sun rotated around the Earth. If you were an inhabitant of modern day Mexico around the same time, reality meant cutting out the hearts of children could make it rain. And if you are an American in 2025, there is a good chance that you believe that one aspect of our reality is that people can be born into the wrong body. In all cases, these beliefs were a matter of what ideas were propagated by that society’s “knowledge forming institutions.” This is covered at length in a very handy little text called The Social Construction of Reality.

People will read that title and think that it means that reality itself is socially constructed. This is not what the authors meant and they go to great lengths in their introduction to explain that what they are talking about is the widely held collection of beliefs which constitute what we think the world or reality is.

So the belief in “reality” ends up being a kind of lazy shorthand where the person saying it ignores just how much of their understanding of “reality” is actually received-opinions from the institutions of their culture. Want to see how naturally the one becomes the other? What’s a country that you have never been to but nonetheless believe exists? It truly is that simple. An astonishing amount of what you consider “reality” has never intersected with your physical experience. It’s no different than when people refer to “common sense” as if it is some real fixed stable of opinion rather than a reference to the common beliefs of a historically situated group of people. I’m no genius, but I’ve read a few books and this stuff doesn’t strike me as particularly hard to grasp.

Folx like James Lindsay and our Mr. Classical Liberal here love to say that anyone thinking like this is being “woke” but that’s just sloppy. All that I’m talking about are the practical implications of epistemological fallibility, a concept that goes all the way back to Plato and the allegory of the cave. In this allegory, people are dominated by illusions which they take to be reality because they do not have access to pure reality itself. Plato saw the job of the philosopher as recovering the real and presenting it to the people inside of the cave, freeing them from their illusions. Socrates (I’m mixing up the timeline here, but it’s just to prove a point) did this by subjecting the ruling authorities and institutions of his time to his particularly adept brand of scrutiny and he found that they just didn’t pass muster. Today we might call this “deconstruction.” James and his fanboys call it “woke.” Incidentally, Socrates did not believe in “common sense” and his entire shtick was that he knew nothing.

There’s an irony here that James and others often talk about the greatness of the Western tradition, but everyone knows that the Western tradition comes from basically two places: Jerusalem and Rome, and the Roman part of that formula begins with Socrates. So if Socrates is “woke” then there is no “unwoke,” and James can only save Socrates from being woke by means of an unprincipled exception (he’s fond of these–see prior point about conspiracies).

We could stay here for longer, but let’s not. Let’s check out point 4. This is the one where the wheels really start to come off.

“Objective moral principles.”

Woo boy. Where to even begin? First of all, I believe in objective moral principles. I just don’t believe that you can know any of them. Let me explain.

If you ever take an epistemology class, there first thing that your prof will do (at least if he’s any good) will be to lead a discussion about what it means to have “knowledge” of something. Eventually, that discussion ought to end up with the conclusion that knowledge means “justified true belief.” You believe something that happens to be true and you are also justified in believing it. This theory usually just called the JTB theory of knowledge comes from Plato’s Theaetetus and is generally considered the starting point for epistemology as a field. Unfortunately, the rest of that semester would probably involve the prof (if he’s any good) walking you through all the different problems with JTB. But we don’t even need to go that far.

Obviously, if there are objective moral principles, then they would probably apply to humans and if that’s true then it’s basically inevitable that there must be some humans who happen to believe in those moral principles. That’s two for three, but getting that last condition is going to be pretty difficult for folx like James and Mr. Classical Liberal. Because unlike proving the number of coins in my pocket or that there is indeed a barn on yonder hill, when I want to justify a moral belief, I don’t get to simply point to the material world and say “See!” In fact, I can’t really appeal to empirical data at all. Shucks, that’s usually how we handle these things. Empirical data isn’t perfect, but it’s damn sexy. And we basically don’t get to use any of it.

If we try to solve the problem by appealing to common sense or our gut intuitions and saying that these are reliable, we run into a problem immediately in that people in different places and different times have differed radically in how they rated the morality of certain things (slavery for instance!) Sometimes people try to square this circle by saying that history has been a process of moral evolution and that we keep getting closer and closer to those true objective truths, therefore our instincts are reliable even though those of our ancestors weren’t. Wherever we disagree, they are wrong and we are right.

Except this seems pretty self-serving, doesn’t it? It implies that we were born morally lucky in that we get to have all our moral beliefs vindicated simply because we happen to be alive at the moment that the conversation is happening. Also, it presents another problem. This conversation is happening now, but it’s also going to continue happening in the future. And if morality is evolving, then maybe it has a long way to go still. People who believe in the moral arc theory of Whig history tend to also harbor beliefs that we’re most of the way to true morality (they don’t always say it but it’s pretty easy to tease out), but what if we’re not even at the half-way point? What if half of your moral beliefs are actually deeply evil based on that final perfected morality? Can you tell which half of the things that you believe are good and right and true are actually stupid and wrong and evil? I didn’t think so.

We could go deeper, but I don’t think it’s necessary. This is an insurmountable obstacle for people who want to argue for an innate moral sense that is both consistent and reliable. The degree to which human morality is consistent across all (or even most) of human history is pretty marginal, stuff like believing that you shouldn’t cut in lines or kill babies. —Oh, hold on just a moment. I’m getting news that that there’s actually a bit of debate about that last one— And if you want to extend it beyond those limited cases, then it becomes immediately obvious that those senses are pretty unreliable since our only measure for reliability is consensus.

So the common sense appeal reveals itself to be firmly planted in sociocultural contingency. And this has been understood inside the field of ethics for a very long time. There have been a number of attempts to create more logically robust defenses of commonsense morality. Kant is probably the most famous as this was his plain intent with The Metaphysics of Morals, which makes it even funnier that Mr. Classical Liberal apparently hates Kant just going to show even further that he has no idea what time it is. But those have all failed too (1). If you want to get a good picture of this failure, I recommend Alasdair MacIntyre. If you want to get more info on how moral principles are actually downstream from hierarchies of values and how those values differ across populations even within a single culture, I recommend Jonathan Haidt.

Let’s try this a different way. Take for a moment this idea of a zeitgeist–the collective value and belief matrix of a given people at a given time. It doesn’t mean that everyone believes whatever is inside of this matrix, but it is the dominant model and basically everyone who does not think seriously and independently about this stuff will basically drift towards this set of beliefs simply as a result of normal socialization. The thing about zeitgeists is that they change. Our current zeitgeist is obsessed gender, race, and equity, but most of these guys (Lindsay et al) grew up during a previous point in the development of this zeitgeist: the 90s.

(A lot of them might object to this and say that their moral scheme is actually coming from the Founding Fathers or 18th century intellectuals who have been mostly forgotten, but they never advocate for any other aspects of the 18th century zeitgeist, and when they do talk about the stuff they’re in favor, it’s all pretty copacetic with the prevailing opinions of the 90s, at least in my experience. So I think there’s a certain amount of salt that must be taken with this objection if and when they make it.)

And for all intents and purposes they have hung on to that zeitgeist, planting their feet and refusing to move along with the times. I don’t really have a problem with this. As someone who got a glimpse of the 90s, they seemed pretty alright. What I object to is the magic trick they use to justify this stuff. And it goes like this.

There is a real world that exists independent of human thought–this alone is not enough to establish anything like objective morality because this external reality does not necessarily have any moral content. Morality is not a part of empirical reality. Go to the site of any evil act that you can imagine and you can measure every aspect of empirical reality that you like, but you will never be able to find where the “badness” is at that scene. So the believer in objective morality or natural law has a problem: he has nowhere to ground his moral impulses.

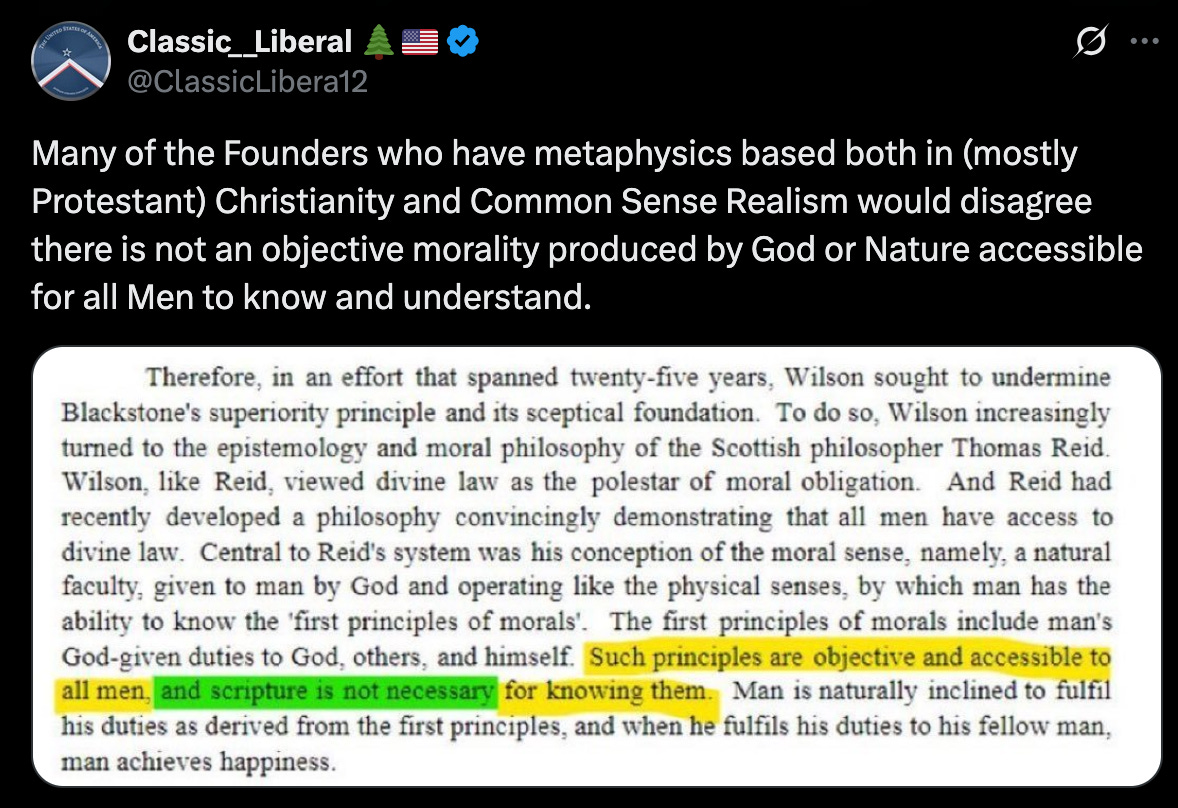

To accomplish this, he has to introduce a new variable: God (2).

God, here only serves the function to secure some possibility of absolute or objective morality. Nature may dictate what Kant called hypothetical imperatives, but it does not provide any “ought” claims that might be described as categorical. Therefore, you need God to bridge this divide. But you’ll never catch one of these guys saying “God exists and so does objective morality, therefore we need a theocratic state to make people follow God’s moral law.” You’ll never even really catch them saying that we need to return to the morality or zeitgeist of the Founding Fathers. No. Instead 90s morality becomes the assumed null hypothesis. You might be thinking that there are some steps missing in this recipe and you’d be right.

My point is simply that this whole formula isn’t exactly what you’d call robust. In fact, it seems like it’s just been hastily constructed out of a particular need to create a boundary around the discourse which makes “common sense” the be all end all of what constitutes Truth.

There is an alternative hypothesis to James’s theory about the “woke” right and left: that both of these groups have simply discovered a true fact about the nature of how power and public opinion/perception works in the world. It’s my opinion that this hypothesis is far more compelling and though I’m not going to run through all of it for this blog post, I think the body of evidence is simply massive. But if James disagrees, he and others will need to produce something a little more defensible than “common sense.”

Rawls’s veil of ignorance was another attempt and probably the most widely circulated in academia today, but it has the same value smuggling problem and it also comes with implications that James and Classical Liberal would find very troubling.

I should note that James Lindsay doesn’t seem to have made this argument himself and probably wouldn’t given that he is an atheist, but it is one that is frequently made or supported by his Christian supporters.

Leave a comment